PLAYER INTERVIEW: Frank "Lefty" Rosenthal

ROBERTO SANTIAGO - cardozaplayer.com.

There are three kinds of people—those who don't know who Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal is, those who are honored to be in his presence, and those who whisper nervously when they catch sight of him. It is the reaction Rosenthal experiences when he enters Prime 112 restaurant, the expensive steak house he frequents almost every day in Miami Beach, located several blocks from his new multimillion dollar two-bedroom condominium. Rosenthal is worthy of nervous whispers. He is, after all, the man Robert De Niro portrayed in the violent 1995 mobster film, “Casino,'' a film revered among those who remember Vegas back in the day.

In the Martin Scorsese-directed epic, De Niro portrays Sam “Ace” Rothstein, a mob-connected professional sports handicapper and bookmaker from Chicago who makes his way to Las Vegas and becomes, through the help of midwestern mob bosses, the most powerful and feared casino boss of the 1970s. But in real life, Rosenthal was even more powerful than his film character. Rosenthal, who made his reputation with the mob for being one of the best professional gamblers of his era, ran not one but four casinos— the Stardust, Fremont, Hacienda and Marina. He ruled them with an iron fist and made them the most profitable casinos on the Strip through a combination of innovative gaming strategies and stellar customer service.

Rosenthal was the first to introduce sportsbook betting in a casino. He was the first to hire women as blackjack dealers. He discovered and promoted a little known magic act called Siegfried & Roy. And whether you were playing nickel slots or dropping thousands on baccarat, Rosenthal's attractive, highly trained staff would make you feel like royalty.

Rosenthal also kept his casinos free of professional cheaters—through techniques depicted in the film. Caught cheating at a table game? You would be taken in the back and have your hand crushed with a rubber mallet. Dare to put your feet on a gaming table? You would be thrown head first out of a window, not a door. Make the mistake of insulting Rosenthal or threatening him? You would be beaten to near death, all while Rosenthal looked down at you, calmly smoking his cigarette and sipping his favorite drink, sparkling water. His security staff handled most of the beat downs, but the most efficient muscle of them all was a boyhood chum named Anthony “Tony the Ant” Spilotro, a wise guy with the Chicago outfit who was very protective of Rosenthal, until the federal government unveiled how the bosses of Chicago, Milwaukee, and Kansas City were skimming money from the Stardust.

While the Vegas of today is run by corporations, the Vegas of Rosenthal's era was ruled by families—mob families such as those of Frank Balistrieri, the mob boss of Milwaukee, and Nick Civella, the boss of Kansas City. They were the ones who secured a $62.7 million Teamster loan—and an additional $65 million loan—so that a young San Diego real estate developer named Allen Glick could purchase the four casinos. Glick was doomed from the start. He never knew that he had to deal with the mob to close the deal. And he would have never imagined that Rosenthal would be the one to call the shots on how the casinos were run. In the end, the feds gave Glick immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony. Rosenthal refused to testify, even after he survived a car bombing, which feds believe was ordered either by the mob—or Spilotro independently.

Born on June 12, 1929, Rosenthal grew up on Chicago's West Side. His mother was a housewife and his father was a produce wholesaler with a knack for mathematics and thoroughbreds. The elder Rosenthal owned several race horses and shared his passion with his son. Not surprisingly, Rosenthal inherited his father's genius for statistics, probability and game theory. From the start, Rosenthal approached gambling as a science: “You don't determine what team is going to win, but what team offers the best value,'' Rosenthal is fond of saying. Beating the odds is hard work, achieved by factoring everything about the two opposing teams. Rosenthal didn't learn this in school. The race track and bleachers of Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park were his high school. The bookmaking houses where he honed his craft were his universities. And legendary professional gamblers like Hymie the Ace, who associated with mobsters but was never part of their world, were his sage mentors.

Rosenthal soon earned a reputation for knowing how to pick the winners in college and professional football and basketball games. It was a skill that attracted the attention of the mob. All Rosenthal offered to these powerful men was one thing: his mathematical ability to pick best-value bets for them. Socially, he never lied to them. He always maintained a professional distance. And he always kept his mouth shut. While most of his contemporaries are either dead or in jail, it was this code of honor that would carry Rosenthal from Chicago, to Miami, and finally to Las Vegas, where he reigned as one of its most powerful figures until the federal government smashed once and for all the mob's rule over Sin City and it all came crashing down.

Today, Lefty's two-bedroom apartment is equipped with all of the cable channels, several TV monitors, and an advanced computer system. Entering Prime 112, Lefty greeted me warmly. At age 76, he is in amazing shape. He was sharply dressed, perfectly groomed, and sported his trademark 4.3-carat diamond pinkie ring. Lefty knew everyone who worked at the restaurant on a first-name basis, and they all knew him. But they all referred to him as Mr. Rosenthal, never Frank and certainly never Lefty. During the interview, he drank several bottles of Panna mineral water and dined on a kobe steak sandwich. He doesn't drink alcohol, but he chain smokes. A lifelong steak and cigarettes man, Lefty insists this beef and tobacco combination is what enables him to chase young women in South Beach, which he calls the Shanghai of America.”

|

PLAYER: After so many years of living in a gated community in

Boca Raton, you recently gave that up for a two-bedroom condo in

Miami Beach. What gives?

ROSENTHAL: I lived in the Boca area close to 17 years and my kids

were grown and had left. The house was a little too large so I decided

to come down to South Beach and get a brand new condominium.

And I'm glad I did. I like the word new. It's a little different lifestyle

out here, a little quicker, a little more nightlife. And it's a good change

of pace from living in sleepy Boca.

PLAYER: So what do you do for fun?

ROSENTHAL: I watch all these good-looking gals parade by that

look like Victoria's Secret models.

PLAYER: And how many do you lasso?

ROSENTHAL: I haven't been able to accomplish that yet, but I am

working on it. Trust me, I am working on it. Pocket and personality

can only get you so far.

PLAYER: But you're a living legend. Getting women should be no

problem.

ROSENTHAL: Next time tell that to those girls.

PLAYER: So what are you doing nowadays to make money?

ROSENTHAL: The same thing I have been doing all of my life.

Studying, handicapping, doing a little consulting work and trying to

find a crack in the line every so often so I can jump in.

PLAYER: And you also do consulting work for the world's top offshore

casinos, the ones that operate online.

ROSENTHAL: I'm with betcris.com, which is the number one book

in the world, without question.

PLAYER: What about bodog.com and betwwts.com?

ROSENTHAL: No, nothing with them. They are still formidable in

Antigua. I don't have any current involvement with them.

PLAYER: When I interviewed you last year, you said that you did

consulting work for bodog and betwwts.com, but they called me and

sent me e-mails swearing that they were never associated with you.

ROSENTHAL: Oh, bullshit.

PLAYER: Why did they deny your involvement?

ROSENTHAL: You know I can't answer that. It's hard to know what

people are thinking and more important, I couldn't care less.

PLAYER: Well, maybe it's your infamy and the fact that companies

like that were being investigated by the federal government in 2005.

ROSENTHAL: I don't have the answer to that question. I don't

know what the interests might be or why they would be interested in

bodog or any off-shore property.

PLAYER: Alleged ties to organized crime, it has been said.

ROSENTHAL: I doubt that. I really do. I know the owner of bodog.

I know the people who work there. In fact I had dinner with him a

little over a year ago in Boca Raton. And he has no association in

organized crime. You can trust me on that.

PLAYER: You know what's strange? As a professional gambler

you don't believe in luck, but despite being heavily involved in the

gaming industry when it was mobbed up—and even surviving a car

bombing—you're still around. Are you smarter than everyone else or

just luckier?

ROSENTHAL: The latter, the latter. Not smarter.

PLAYER: You have to miss the old days.

ROSENTHAL: How so?

PLAYER: Throughout the 1970s you ruled Las Vegas, and everyone

respects that.

ROSENTHAL: Vegas was fun—I enjoyed my time there.

PLAYER: Before we start getting into the Vegas years, let's talk about

growing up in Chicago. What drew you to become a professional

gambler?

ROSENTHAL: My father was in the horse-racing business. He

owned thoroughbreds when I was in high school. That was my first

attraction. And sports in general became my first love. I'd go to

Wrigley Field to see the Cubs instead of going to school every day,

and in the evening I'd go to Comiskey Park for the White Sox. I was

a regular at Chicago Stadium whether it would be hockey or NBA or

college basketball and it all became…I just got focused on it. And not

just focused, but trying to find a way to beat the odds. Which was

not easy.

PLAYER: You don't gamble, you study. Do you think people who go

to casinos are suckers?

ROSENTHAL: No, I don't consider them suckers. I really don't.

Conversely, no human being—zero—can beat a casino. Anyone who

says he can is a liar.

PLAYER: Not even you?

ROSENTHAL: No, not on the straight. You could cheat, sure. But

you can't go up against those odds on a crap table or roulette. You can

get lucky, but not on a regular basis. It's mathematically impossible.

There are no exact statistics, but as an educated guess less than one

percent of the public would be eligible to win. Much less than half a

percent can make a living from this game.

PLAYER: You left Chicago to come to Miami in the 1960s. But then

you were run out of Miami because you were running a bookmaking

operation. Why didn't you pay off the cops to stay in business?

ROSENTHAL: No, I wasn't bookmaking. That's not true. When I

moved to Miami from Chicago I bought some yearlings and some

thoroughbreds. I was gambling, handicapping, but not booking.

PLAYER: But from what I've read I always understood you were

the biggest bookmaker in Miami, and you were chased out of town

because you wouldn't pay off the Miami cops.

ROSENTHAL: No, I was high profile from my gambling days in

Chicago. The Miami cops thought I was a Chicago bookmaker—

which I was not. The fact is I was doing two things: working with my

thoroughbreds—I was licensed—and handicapping. And neither is a

crime. They are both legit. But there were politicians and cops who felt

otherwise and tried to shake me down. I was arrested in North Bay

Village in Miami, charged with bookmaking—but the charge was

subsequently dismissed.

PLAYER: But there are true-crime books, documentaries, and reams

of federal documents that say you were a bookmaker and had ties with

organized crime all of your life. What do you say to that?

ROSENTHAL: They are all wrong.

PLAYER: In fact, recently released federal documents say that in the

1960s you were associated with a CIA-connected, Cuban-American

anti-Castro militant named Luis Posada Carriles. He's the guy wanted

by Venezuelan authorities for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner

that killed 73 people. And he is wanted by Cuban authorities for a

string of bombings in Havana that killed an Italian tourist and injured

six people in 1997. The feds claim that back in the mid-1960s you

forced Carriles to give you hand grenades, silencers, detonators and

fuses that you in turn passed to the Chicago mob. [Rosenthal is shown

several newspaper articles about these allegations].

ROSENTHAL: I've seen that. And I have no idea what you're talking

about.

PLAYER: Is this all fiction?

ROSENTHAL: I'm not going to go into it.

PLAYER: These same documents claim that you were under

investigation by the Justice Department for seven car bombings that

took place—shortly after dealing with Posada—in the Miami area.

ROSENTHAL: Again, I said I am not going to go into it.

PLAYER: Okay, tell me about Frank “The German'' Schweihs, the

75-year-old hit man on the lam from the FBI. He lived in Dania

Beach, Florida, up until April 2005—but disappeared the day before

the FBI launched its biggest mob bust, “Operation Family Secrets,''

indicting 12 reputed Chicago crime members. In the book “Casino,''

you described Schweihs as a really dangerous guy.

ROSENTHAL: Let me correct myself. I knew Frank very well.

Dangerous would not be the right word. Frank

was a rough character. He wasn't the kind of

guy you'd want to mess with. He could handle

himself quite well. My experience with him?

We were very friendly. I don't know how I

met him. It might have been through Tony

[Spilotro] at the time. We became friends and

stayed friends while I was in Chicago.

PLAYER: What about Joey “The Clown”

Lombardo, a Chicago crime boss who is also

on the lam from the FBI?

ROSENTHAL: Same circumstance. Joey was

one of the guys I played handball with in the

YMCA. Good guy as far as I was concerned.

We had no professional relationship. It was

strictly “Hey, how're ya doing?” And literally

handball. He was a good handball player.

PLAYER: Were you surprised that they were the only ones who

managed to escape the FBI when the feds cracked down on the

Chicago mob last year?

PLAYER: Were you surprised that they were the only ones who

managed to escape the FBI when the feds cracked down on the

Chicago mob last year?

ROSENTHAL: I didn't know they escaped.

PLAYER: Well, they disappeared. Rumors are that they may be hiding in

the Caribbean. [Editor's note: Schweihs was arrested in Kentucky

in December 2005, several weeks after this interview.]

ROSENTHAL: They are both smart. And smart people don't allow

themselves to get caught.

PLAYER: Any colorful tales about Schweihs and Lombardo?

ROSENTHAL: The only thing I remember with Joey was one day

I was in the YMCA and I thought I could beat him. He was a good

handball player. So I tried playing him with a racquet. I tried and I lost.

And as far as Frank, I recall he opened up a steak house in O Town in

Chicago. I think it was called the Meat Block. It was good. Frank had

a good sense of humor, but that was the extent of the relationship.

PLAYER: Was Schweihs close to Tony Spilotro?

ROSENTHAL: I don't know if he was.

PLAYER: Close enough that federal law enforcement believes that in

1986 Schweihs was one of the Chicago mobsters that killed Spilotro

and his brother Michael, beating them to death and then burying them

in a cornfield.

ROSENTHAL: I don't know about that. Our relationship was strictly

social.

PLAYER: He also allegedly murdered Allen Dorfman, who ran the

Teamsters Union pension fund, the same Dorfman who bankrolled

the four casinos that you ran in the 1970s.

ROSENTHAL: I don't know about that.

PLAYER: You dealt with underworld characters, killers, mobsters, but

you never became a part of it. You were a Jewish man among Italian

mobsters. Did your heritage protect you from being a made man?

ROSENTHAL: No, when you excel at anything—my expertise was

sports and thoroughbred wagering—you rise to a very high level. Some

people were impressed and took special notice that I could beat the

odds. To have recognition, in my judgment, opened certain doors for

me. It put me in a semi-celebrity category.

PLAYER: But in order to move ahead you had

to deal with the mob mainly because, during

your era, they were involved in all aspects of

the gaming industry.

ROSENTHAL: Well, I was never a part of

them, but I made it a point not to burn any

bridges. I don't see any purpose in burning a

bridge.

PLAYER: Especially with them.

ROSENTHAL: If you keep your distance, you

keep your independence. Provide them with

the service that attracts them to you. In specific

areas I did have an aptitude at a high level

when it came to the mathematics of accurately

determining the probable outcome of sporting

events. That is an attraction and it snowballed.

Yeah, when I left Chicago at the age of 31 and moved to the Miami

area I had a very high profile. Most of it not because of who I knew,

but gambling, gambling, gambling. The same applied when I went to

Las Vegas. You take the word gambling and you combine it with the

word Chicago there is a perception that you might be something that

you're really not.

PLAYER: The book “Casino” states that Milwaukee crime boss Nick

Civella flew you and Allan Glick into Kansas City at 2 a.m. for a

meeting where he laid it on the line, threatening Glick that you were

the boss of the casinos and not him. Is that true?

ROSENTHAL: Never happened.

PLAYER: So why did writer Nicholas Pileggi, a highly respected crime

author, put that in the book?

ROSENTHAL: Nick is a good guy. I can't recall ever reading that in

the book.

PLAYER: Look, here it is on page 138 of the hardcover edition.

[Rosenthal is shown the page.]

ROSENTHAL: It's possible that he doesn't have all of the facts. Allan

Glick was trying to get an additional loan from the Teamsters, but that is my recollection of what

happened in Kansas City, not what you described.

PLAYER: Since we have the book out, what about page 135, where you

told Glick: “If you interfere with any of the casino operations or try to

undermine anything I want to do here, I represent to you that you will

never leave this corporation alive.”

ROSENTHAL: Never happened, for sure.

PLAYER: When Glick testified under immunity in the Stardust skimming

operation, he said a lot of things. Was he lying?

ROSENTHAL: All I can say is that I don't know any of the arrangements

he had.

PLAYER: Did you know about the skimming operation at the Stardust?

ROSENTHAL: Negative. If I did, they should have charged me. But they

never did. I learned about it when the indictments took place.

PLAYER: That's one thing people don't realize—although dozens of

federal documents imply you were crooked, you were never arrested or

indicted.

ROSENTHAL: If I were guilty I would have been. I submitted myself

to endless hours of interviews regarding the skim operation. If they had

something, they would have dropped the hammer on me. But they had

nothing other than innuendo. Remember, while gaming is considered the

number one industry in Nevada, it's not. Bullshit is number one. Gaming

is second. That's the truth. Bullshit is what that town is all about.

PLAYER: One thing for sure—running a Las Vegas casino back in the day

was tough. What are the fundamental skill levels required for success?

ROSENTHAL: You need man-power and brain power. It was difficult to

find good employees in that state. So if you demand 16 ounces to the

pound you are challenged. You are criticized as being a perfectionist.

PLAYER: And you were. Didn't you demand that each blueberry muffin

your chef baked at your casinos have an equal number of blueberries?

ROSENTHAL: Yes, it's true—that was in the movie.

PLAYER: Speaking of “Casino,” did Tony Spilotro ruin your career?

PLAYER: Speaking of “Casino,” did Tony Spilotro ruin your career?

ROSENTHAL: He didn't ruin it, but he certainly didn't help it. When

he moved to Las Vegas there were those who felt that he was there on my

behalf. Not true. He was there on his behalf, not mine. But because of our

previous relationship he did make things warm for me there and may have

been the single most reason that increased the heat.

PLAYER: In the film, Joe Pesci plays the Spilotro character. There's a

scene where he stabs a man in the neck with a fountain pen. Is that true?

ROSENTHAL: Yes, we were at the bar at the Stardust. I'm no drinker, and

a fellow next to me had been drinking too much and there was a fancy

fountain pen that rolled over my way from him. And I gently tapped him on

the shoulder and asked him if the pen was his. He didn't like the question

and I guess his frame of mind wasn't level. He made a few comments to

me. Tony took exception to it, and he gave him a hard time.

PLAYER: Did Spilotro stab him in the neck?

ROSENTHAL: I don't recall exactly how it was done, but the guy did go

down quick.

PLAYER: Ever since you and Spilotro were kids in Chicago, you had that

kind of relationship. He would watch your back—right up through the

Stardust days.

ROSENTHAL: Well, if you are asking me if he was my human German

Shepherd—no. But at that time we were pretty close and I guess he felt an

obligation to watch my back.

PLAYER: What about the scene in “Casino'' where you ordered a card

cheat's hand to be crushed?

ROSENTHAL: Oh, that's true. I was coming in for the night shift and

I noticed that a blackjack table had a huge crowd around it. I walked

over and took a look and there was one player who had $75,000 in chips

in front of him. I looked over to the pit boss and asked, “What's going

on?'” And he shrugged like the guy was getting lucky. Something told me

that he had a hot hand. Why? Because he wasn't losing—that's why. So

I knew something was wrong. I saw the player at the opposite side of the

table was wiring electronically the dealer's hole card to the winner. I had a

security man zap the sender with a cattle prod. It was powerful. The sender

went down hard. We pretended to help him back up and took him to the

woodshed—that's what we called the back room—and at first he pleaded

not guilty. And then he very quickly changed his mind when we strip

searched him and asked him what the wiring to his leg was all about. He

had a little device where he tapped out messages to the receiver.

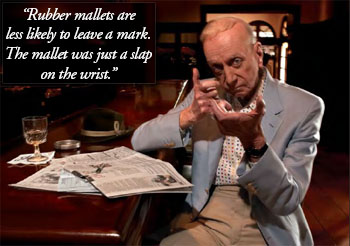

PLAYER: Then you ordered security to crush the sender's right hand,

making him a lefty. Why did you use a rubber mallet instead of a metal

hammer?

ROSENTHAL: Rubber mallets are less likely to leave a mark.

PLAYER: Would a hammer mark trace you to law enforcement if the card

cheat went to the cops?

ROSENTHAL: Yes, that was the thinking. He could have. He didn't. He

was lucky he got out of there. Trust me. He was lucky. It wasn't just two

guys—it was a well-known gang that was ripping off casinos. I wanted to

send a message: Don't come in here. We told them that the next time it

wouldn't be a mallet.

PLAYER: What would it have been?

ROSENTHAL: I'm not going to say—but the mallet was just a slap on the

wrist. We went easy.

PLAYER: What about the sender?

ROSENTHAL: We told him he could either leave or cash in the $100,000

worth of chips and stay in the room with the mallet. He left.

PLAYER: Would you have given him the cash if he took the mallet?

ROSENTHAL: No.

PLAYER: So what gets casino cheats in the end is greed.

ROSENTHAL: Always. Had they played less and pretended to lose and

leave with a few thousand they could have beat us on a regular basis. It's

called milking. The best cheats make a career by milking. But their luck

runs out too. Every cheat's does.

PLAYER: Back in Chicago you saved Tony Spilotro's life. Fiore “Fifi”

Buccieri, the boss of the West Side, was strangling Spilotro because he

thought Spilotro was mouthing off to him.

ROSENTHAL: I talked Buccieri out of it.

PLAYER: But Spilotro went from being a close friend to your nemesis. He

made things tough for you in Vegas, had an affair with your wife. When

you heard he was beaten to death and buried in a cornfield, what was your

reaction?

ROSENTHAL: I'm glad I wasn't asked to be one of his pallbearers.

PLAYER: Your marriage to Geri McGee, who Sharon Stone played in the

movie, I think can be summed up in one phrase: “Lucky in cards, unlucky

at love.” What was so special about Geri?

ROSENTHAL: They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. And in Geri's

case, no matter who the beholder was, she was drop-dead gorgeous.

PLAYER: But she was like the female version of you—a hustler who used

men to get what she wanted. Like you, she couldn't be controlled. You bet

on a long shot.

ROSENTHAL: I didn't know. I found out later.

PLAYER: But she was one of the best hustlers in Vegas at the time—if

not the best.

ROSENTHAL: I felt I could change anyone. I was wrong. Not her.

PLAYER: Did you ever re-marry after that?

ROSENTHAL: No, I never met the kind of woman that I had that same

intense interest in. But never say never.

PLAYER: You always had a code of ethics that I think kept you alive. You

never snitched. You never accepted government immunity—even after

you survived a car bombing.

ROSENTHAL: True. The Vegas Metro police came at me hard after the

bombing to cooperate, and said they wouldn't protect me if I didn't.

PLAYER: And you said no? But someone tried to kill you. Most people at

that point would have cooperated with the government.

ROSENTHAL: Yes, my attorney then—Oscar Goodman, who is now the

mayor of Vegas—told me the day after the bombing: “After this, whatever

you decide to do, I don't blame you.”

PLAYER: You are one of the few people ever to survive a car bombing.

ROSENTHAL: It was a rough night.

PLAYER: Who did it? Spilotro? The Chicago mob? The motorcycle gang

Geri ran with?

ROSENTHAL: It remains unsolved. Who do I suspect? I don't want to

go on the record with.

PLAYER: You don't snitch. Why?

ROSENTHAL: It all comes down to style and doing what you feel

comfortable with. I never talked about or testified against anyone and never

will. An attempt on my life would not change that. I have no regrets.

PLAYER: What do you miss about the Vegas days?

ROSENTHAL: I miss the money and the challenges of running a casino.

We had a top operation. We had a first-class ship, second to none.

PLAYER: And you never succumbed to the violence of that world.

ROSENTHAL: I was meant to survive with my mind. Why I survived? I

hate to say it—but it was luck. I'm a very lucky man.

PLAYER: I understand that although you are in the Black Book, banned

from running a Vegas casino or even entering one, you still sneak into

Vegas casinos?

ROSENTHAL: I sure do—to see what's going on. But I haven't been to

Vegas in three years.

PLAYER: How do you disguise yourself? A fake beard?

ROSENTHAL: I better not give you all of my secrets.

PLAYER: Ever go to the Stardust?

ROSENTHAL: I'm always tempted—but something tells me they would

spot me.

PLAYER: What is your opinion of the new corporate Las Vegas?

ROSENTHAL: The corporate takeover? My personal opinion is that when

I was there it was better. You treated customers on a one-to-one basis.

Customer service was key. Today, while they offer spectacular casinos and

amenities in those properties, it's not first class. If you happen to be a

whale you are treated well. But anyone else, they couldn't care less.

PLAYER: Your opinions of two high profile casino owners: Steve Wynn?

ROSENTHAL: The smartest casino owner out there right now. The

biggest operator, no question about it. We are friends. His Wynn casino

is the best out there.

PLAYER: Donald Trump?

ROSENTHAL: I don't know him, but based on his casinos filing bankruptcy,

it is clear casinos are not his expertise. Hotels, yes; casinos, no.

PLAYER: Let's talk about your innovations. When you ran Vegas, you

were the first to put a sportsbook in a casino.

ROSENTHAL: Yes, we were the first to build the prototype for sports

wagering and it just took off. It was a king-size undertaking on my part.

No one thought it would work.

PLAYER: The industry had that attitude when you decided to train and

hire women as blackjack dealers.

ROSENTHAL: Very true. There was this old-world mentality that women

couldn't do the job—that they were only good enough to serve cocktails

or be showgirls—which was nuts. When we had female dealers it increased

the pot instantly. It was a no-brainer: You are a guy? Who would you

rather have in front of you as a dealer? Women proved to be our best

dealers from the start. We made more money. They were better dealers.

They knew men and how to handle them. And men didn't seem to mind

losing more to them.

PLAYER: Who do you still keep in touch with from the old days?

ROSENTHAL: Very few. There are a couple in Vegas—two or three who

I'd rather not mention. Time moves on. Things change.

PLAYER: Ever get tempted to enter the gaming industry down in Florida?

Maybe when pari-mutuels get slots later on in 2006?

ROSENTHAL: No, I am happy with what I am doing. My head is above

water. I'm making a living.

PLAYER: You once said professional gamblers look for value, players look

for winners.

ROSENTHAL: True. Value is a tangible item. Gaming is subjective, but if

you're determined you can judge what is a better value. Get the information

prior to it becoming public—the inside information. Professional gamblers

do not gamble, they make informed decisions. Knowledge—that is value.

Players do not make informed decisions. They are relying on luck, fantasy,

wishful thinking.

PLAYER: Is that what keeps the gaming industry alive—luck and

fantasy?

ROSENTHAL: Absolutely.

PLAYER: What do you think of the poker craze?

ROSENTHAL: It's phenomenal. The public, for whatever reason, has

fallen in love with poker. I think it's because poker is the one game that

can be played in commercial casinos, pari-mutuels, Indian casinos, and in

one's home. It's a social game that requires skill. It has attracted women. It

has attracted young people and celebrities. It is seen as a sport. When you

have all of those crossover factors, it means success. How much longer it

will last, who can tell?

PLAYER: Now here is something that will surprise a lot of people. You

only saw “Casino” once—and you don't like the movie.

ROSENTHAL: It lacked the detail of what I did. There are scenes where

the Rosenthal character repeated the same thing twice. I would only tell

you to do something one time—that's all I needed. And there was that

scene that still angers me when I think of it—I never juggled on “The

Frank Rosenthal Show.” I resent that scene. It makes me look foolish. And

I only did that TV show on the behest of the chairman of the board of

the Stardust so that the public would realize I was a decent guy and not a

mobster as portrayed by the media covering us at the time.

PLAYER: You've lived an amazing life. What do you hope your legacy

will be?

ROSENTHAL: That I was a good father and that I contributed a little

something to the gaming industry.

Copyright © 2006 Avery Cardoza'a Player Magazine. All Rights Reserved.

Takeing from cardozaplayer.com.